Andean community approach on drugs

Enfoque comunitario andino sobre las Drogas

Revista PERSPECTIVAS

EN INTELIGENCIA

Carlos Enrique Vargas Villamizar 1

(1) Universidad Externado de Colombia, Bogotá – Colombia, carlos.vargas@unimilitar.edu.co

Volumen 13, Número 22, Enero - Diciembre 2021, pp. 137-152

ISSN 2145-194X (impreso), 2745-1690 (en línea)

Bogotá D.C., Colombia

http://doi.org/10.47961/2145194X.275

Fecha de recepción: 09/05/2022 | Fecha de aprobación: 18/05/2022

Abstract

According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy of the White House, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia produce the totality of cocaine that is exported to consumer countries all over the world. However, after many years trying to reduce the plantation of coca plants in these three countries, it has been observed an increase in the records of the cultivations during the past ten years. This article assesses the policy to fight against the drug phenomena through an international collective approach, materialized in the Andean Community of Nations. Also, it is proposed a cause to the increase in the coca plantations despite the efforts of the national governments and international organizations.

JEL classification: F02, F52.

Keywords: Andean Community of Nations; Narcotic Drugs; Cocaine; Communitarian Security.

Resumen

Según la Oficina de Política de Control de Drogas de la Casa Blanca, Colombia, Perú y Bolivia son los productores de la totalidad de cocaína consumida en todo el mundo. Sin embargo, después de muchos años de lucha para intentar reducir las plantaciones de hoja de coca en los tres países, se ha observado un incremento en los indicadores de cultivo en los últimos diez años. Este artículo analiza la política de lucha en contra del fenómeno de las drogas a través de la perspectiva colectiva internacional, que se materializa en la Comunidad Andina de Naciones. Igualmente, se propone una causa al incremento en los cultivos de coca a pesar de los esfuerzos de los gobiernos nacionales y las organizaciones internacionales.

Palabras Clave: Comunidad Andina de Naciones; Narcotráfico; Cocaína; Seguridad Comunitaria.

Introduction

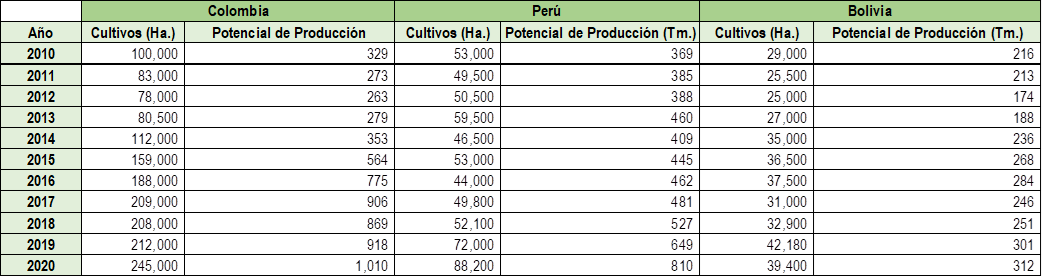

On March 2017, the Colombian government waited with impatience the report from the Department of the State of the United States announcing the increase in the coca production in the country in levels that were never seen before. This report overshadowed the general mood in the country after the signature of the peace accords and put pressure on the Colombian government to put forward a policy against drugs that shows determining results on this matter. Afterwards, announcements coming from the president Santos government exposed a particularly solid position on the willing of his government to do whatever is necessary to reduce the supply on drugs and accusing the demand of cocaine in the United States as one of the most relevant causes for the persistence of the drugs problem. This marked the first verbal encounter between the Trump and Santos administrations, creating some tensions in the bilateral relations of two old-allies. Nevertheless, during the Biden administration, a new record was set, reaching 245.000 hectares in 2020 (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2021).

In this regard, the illicit drug issue came to be first in the political agenda of the Colombian government after being mostly focused on the implementation of the Peace Agreements with the FARC[1]. Nevertheless, how it is widely accepted nowadays, the problem on drugs is a global matter that has many multidimensional links, going from state corruption to financially sustain criminal organizations, and equally affects many countries in the world, from production to transit and consumer countries. Therefore, for being a transnational problem, the illicit production, trafficking, and consumption of drugs must be addressed in a transnational manner. There is nothing a country alone can try to do on this and expect to have efficient results. Having this into account, many international instruments have been prescribed inside the mechanisms of global and regional platforms to better understand and tackle this phenomenon[2] from a multilateral perspective. However, this problem especially touches and affects the Andean Region, given that the total supply of cocaine in the world is produced in this region. As a matter of fact, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia have the monopoly on the production of coca (See annex 1). This has implicated long years of violence, institutional corruption, underdevelopment, economic informality and environmental damage in these countries, given the criminal action of organizations that control the production, traffic and illegal sale of illicit drugs. Such situation has largely affected their national perception and institutional development, both nationally and internationally, as their violence indicators increase and a great part of their public budget need to address such problems.

One interesting particularity of this situation is that these three countries are grouped in the Andean Community model of integration. Having this into account, it is important to ask, to what extent the common agreements on the drug problem in the Andean Community have impacted the production of cocaine in the member states? To answer this question, the following article will address that the coca production in the Andean countries has responded to a historical and cultural framework that has shaped the different conditions of their illegal activity on drugs. Thus, under the acknowledgment of this transnational problem, the Andean Community has produced supranational instruments to better approach and understand the illicit production of cocaine[3]. However, national specificities combined with the institutional inability to effectively put in practice the agreements have not only failed in reducing the supply of cocaine in the world but also established a mistrust in the multilateral intervention to the drugs issue, favoring the consolidation of an illegal production system in the region.

This article, will address the issue presented through the analysis of academic literature to better expose the characteristics of the matter to the reader. First, a context of the situation of coca securitization process in the Andean Region is presented. Then, the article concentrates in analyzing the mechanisms to fight illicit drugs that are contained in the Andean Community. Finishing, by assessing the main obstacles to the communitarian approach and suggesting a forecast the next five years.

Drugs in the Andean Region

In order to understand the current problem of narcotic drugs in the Andean region, it is important to address the historical evolution of the illicit production and trade of psychoactive substances. From ancient times, coca plantation was not related to illegal activities. In fact, coca plants are essential to the cultural development of indigenous communities that inhabited and still make a presence in the Andean countries. Here, the first obstacle related to the problem is found. Given that coca plants have a legal use for cultural practices of constitutionally protected groups, the process of eradication and substitution must have into account the demands and the interest of those that need coca leaves to protect their traditions. As well, countries like Bolivia categorize the coca plant as part of the natural medicine of indigenous communities and attempt to use such medical properties to develop a more comprehensive understanding of medicine (Guerrero, 2013). However, this poses a problem, in the sense that illegal groups may take advantage of ancestral groups to hide illegal activities and maintain the supply of the product (Mansilla, 2009, p. 101). Nevertheless, it is important to indicate that even if coca plantations are legal, and protected, cocaine is still illegal, due to the instrumentalization of cocaine to financially support criminal organizations and rebel groups, as the harmful and addictive effect that it has to the consumer, leading to death in cases of overdose.

The global problem on drugs can be traced back to the Nixon administration (1969-1974) when he declared the war on drugs to tackle the exports of cocaine, opium, and marijuana that would finance communist guerrillas in Latin America (Diaz, 2002). This was based on the increase in the consumption of cocaine, and other drugs, in high spheres of the American society at the end of the sixties. Such demand encouraged an increase in the production of coca plantations in Bolivia, Peru and the beginning of the use of cocaine to finance illegal groups in Colombia. Therefore, the increase in the demand of this new drug in the United States and Europe prompted an increase in the supply from the Andean countries, which were accompanied with the complexification and specialization of the phases of plantation of coca leaves, transformation to coca paste and cocaine, international traffic and illegal sale. This also caused an increase in the violence perceived in these countries and the militarization of the problem.

The process by which an issue enters the security agenda is known as securitization. This term of the School of Copenhagen is a specific grammatical process that presents an issue as an existential threat to a designated referent object through speech act (Buzan et Al. 1998, p.21). This is done in order to justify extraordinary measures in order to maintain security, given that the mere enunciation of security creates a social order wherein normal politics are bracketed (Balzacq, 2005, p. 171). This practice takes place through the interaction of an audience that is persuaded by a speaker in a given configuration of circumstances (p. 172). A common represented example of securitization is the identification and the political adoption of the Drugs on War both globally and domestically in the United States (Campbell, 1998). This, through the political instrumentalization of drugs sustained by powerful political groups that are able of construct and maintain a securitization speech to the public given a certain context.

Furthermore, international organizations have helped to establish a legal and political framework to define drugs as an existential threat. The United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances are both examples of ‘speech acts’ to develop a new comprehension on the problem of drugs as a threat against the life of individuals, the morality of the states and international peace (Crick, 2012). National policy frameworks have adopted such conventions and have identified drugs as a security matter, even if their conditions of possibility are not determinant. On the contrary, the objectification and externalization of danger through foreign policy need to be understood as an effect of political practices (Campbell, 1998, p.16). As well, the United States strategy on Drugs has not only establish an identity to that nation’s foreign policy but has imposed an identity to countries like Colombia and Mexico as narcotic countries, which has several implications in the culture of certain communities (Martinez, 2012).

In this regard, discourses coming since the Nixon administration (1969-1973) have defined the drugs as the ‘public enemy number one’ for the security of the state and the public health of its citizens (Martinez, 2012, p.247). Furthermore, production countries were regarded as inefficient deemed as corrupt, and with the necessity of the help of the United States to be protected and put an end to the narcotic drugs issue. Then, such narratives coming from international platforms and hegemon countries have not only given identity to them as ‘benevolent’ actors but have to define Colombia and Mexico as dangerous and violent places. These discourses have been translating into the donation of economic and technical aid, that in the case of Colombia, with the Plan Colombia (2000-2016), meant the militarization of the issue, increasing the levels of violence.

In fact, illegal drug production in Colombia is managed and carried out by hierarchically organized armed organizations that use violence against other criminal organizations, or security authorities of the State, to gain and maintain control over production zones and traffic corridors. As it has been proven, insurgent guerrillas in Colombia such as the FARC or the National Liberation Army (ELN) perceived revenues from the plantation of coca crops and even from the transformation of cocaine and its illicit traffic to Europe and the United States. However, it is the discourse around that production, and the use of violence, that has been characterized to be an existential threat. The adoption by the public and the continuation of the political discourse have naturalized the drug discourse in Colombia. By taking the social construction of drugs organizations as a natural and constant threat, the construction is obscured and they are accepted as reality (Weldes et Al., 1999, p.14). The naturalization process has been such in this country that not even the extreme left political parties put in doubt the need of tackling crime organizations with the coercive capabilities of the State. This can be observed in the Peace Agreements between the Government and the FARC, that established mechanism to reduce the supply of cocaine both through a voluntary and forced substitution (Final Agreement, 2016, p.96).

Nevertheless, the improvement in the production of illegal drugs was different in each country of analysis, affecting the current conception of the problematic, and shaping a different framework from one country to the other. The difference of conception on the problematic opens a difficulty for the regional approach on the illicit drugs issue. In this order of ideas, the success of the regional action on drugs has a direct relationship with the strength of the organization. After analyzing the particularities of each country, this paper is going to focus on the lack of pragmatism and capabilities of the Andean Community to execute an effective regional policy on drugs.

In Bolivia, the cultivation of coca leaves is a traditional and legal activity which fomented the definition of traditional production zones used by indigenous communities, transition zones in process of substitution, and illegal zones. This encompasses a sort of gray zone between the legality and illegality of the cultivation and processing of coca leaves. In this country, there are illegal practices in specific phases of the production, which ends in the illegal traffic of substances to export to transition countries. Such problem is enlarged by the lack of abilities and disposition of the authorities and regulatory systems to control the issue. In any case, coca production in the country has deep implications in the institutions of the state, having roots in legal, moral and cultural constraints that restrain the coercive action against illegal activities (Niño, 2011). Just to enlighten the reach of the state of affairs in Bolivia, one has to analyze the political muscle of the well-organized coca labor unions. Some of these unions count with a political structure centralize in the Movimiento al Socialismo political party. The president Evo Morales is affiliated to this party since the beginning of his political path. The existence of such a political party that encompasses the demands of the cocaleros[4] and acts in function to the government is one of the most important causes for the increase in the supply of coca leaves and even for the innovational improvement that helps transform it into illegal substances.

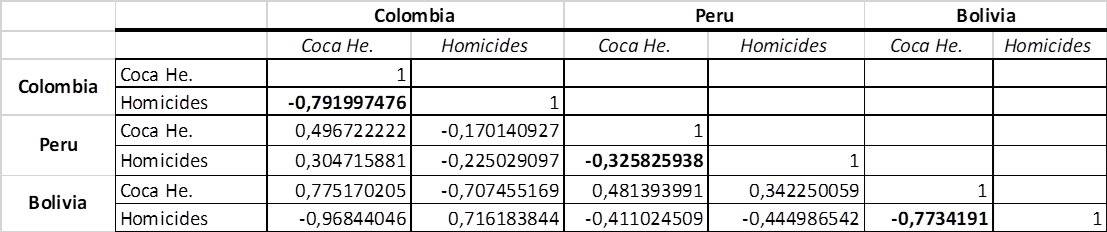

In Peru, the coca cultivations fields exceeded those in Colombia and Bolivia in most of the twentieth century due to the presence of rebel groups that controlled large part of the Peruvian territory. However, criminality is not organized in this country, being mainly small groups the ones in charge of the production and traffic of coca derivatives and cocaine (Niño, 2011). On the other hand, the criminality perception has increased in the past ten years affecting the credibility of the state’s authorities. The border with Colombia is one of the regions with most plantations on both sides of the frontier. This is used by criminal organizations to maneuver against unilateral actions of Colombia or Peru. Nevertheless, this country has had successful experiences on alternative development, and somehow the big amount of plantation of coca has not inflicted an increase in the homicides or the full penetration of cartels in the private and public institutions of the State (See Annex 2). Still, security agencies have not a robust capability to deter illegal organizations and inflict important damage on them, despite the increase in the counternarcotics budget during president’s Humala administration. Therefore, the levels of coca production seem to respond more to the balloon effect, an externality causing the increase of coca plantations in one territory given the decrease in other, with Colombia or the situation of the international demand. In the report of the Department of State of United States (2017) the Peruvian cocaine is categorized as to be mainly exported to other South American countries for domestic consumption (Department of State., 2017, p. 239).

On the other hand, in Colombia the problem of the drugs in very militarized, based on the influence of the United States foreign policy in the country, increasing the levels of violence and helping the consolidation of illegal structures that interacted in the Colombian armed conflict (Diaz, 2002). The pre-existence of mafias in different illegal business eased the penetration of the cocaine production in the country (ibid.). The interaction of such organizations, that goes from the Cali and Medellin Cartel to the FARC and AUC[5], to control territories and routes for export, established an extremely violent framework in Colombia related to drug trafficking (Niño, 2011). In Colombia, the revenues of the illegal drug penetrated deep in the public and private institutions increasing corruption perception and affecting the fight against narcotic drugs for several years. As well, this issue has been in the center of the relation with the United States, a country that is essential to the Colombian foreign policy.

Currently, the drugs policy is central to the successful and peaceful development of the post-conflict, where the reduction and substitution of illegal crops were a main point in the Peace Agenda. Therefore, efforts are focused to reduce the highest coca field levels in the history of the country and reduce the violence that the fight between organized crime groups and the government has left (Jelsma and Youngers, 2017). The plan is targeting to remove 100.000 hectares of coca crops in 2018, 50.000 through substitution development programs and 50.000 through manual eradication of the plans. To each family that voluntarily remove coca plantations the government is going to subsidize 700 dollars a month for one year and will provide technical assistance to replace illegal crops with legal ones (Semana, 2017). However, in the next session, this paper will address the difficulties had to achieve such ambitious goals.

In this order of ideas, the different frames of productions and conceptions in Bolivia, Colombia and Peru about coca plantations, configured the institutional approach to the question, as well as the illegal groups' response. Then, the violence related to organized crime and illicit drugs trafficking is different in each country, being almost imperceptible in Bolivia and almost escalating into war levels in Colombia. Even, in 2010 when Peru surpassed Colombia as the largest producer of coca in the world, the levels of violence in the two countries were extremely different. This is due to the presence of organized mafias in Colombia with a specific stock of violence[6]. Also, the prominence of violence in Colombia is a result of the presence of two or more groups that dispute the territorial control in strategic production zones (Cubides, 2014). As a result, Bolivia and Peru present fewer levels of violence given that they are coca producers countries mainly controlled by farmers, meanwhile in Colombia there are many more armed groups that transform coca into cocaine and export it to North America and Europe having more armed and corruption capability.

Andean Community Approach to Illicit Drugs

The Copenhagen School of Critical Security Studies proposed a very convenient theory to approach communitarian threats. From the contributions of Buzan, Waever and de Wilde (1998), it can be understood the tight relation among states in the regional level referring to security threats. The concept of Regional Security Complexes is defined as the conjunction of States, whose security perceptions and preoccupations are so interrelated, that their security problems cannot be rationally assessed or resolved in an individual manner (Buzan et al, 1998). Then, the international character of security can be comprehended, and the shared responsibility of states regarding threats can be assessed. Given that a threat to one State can in fact affect their neighbor, the best manner to approach it is through a joint strategy. From this perspective, it is clear where the necessity for cooperation and communitarian security comes from. Specially, in the matter of illicit drugs trafficking, that takes advantages of border porosity and differences in normative bodies in order to conduct their criminal activity.

Having this into account, a regional perception of the problem is needed to standardize a more comprehensive national and regional approach. In this scenario, is where international organizations, such as the Andean Community, serve as platforms to better proceed against the production and export of illicit drugs. The perception of organized crime and illicit drugs traffic as a transnational issue that goes beyond national particularities is not new. Since 1988, the General Assembly of the United Nations consolidated the global problem of drugs in the Vienna Convention. Moreover, in 1985 the Andean Parliament declared narcotics traffic as a crime against humanity by the generation of social, economic, cultural and politic problems. The year after, the Rodrigo Lara Bonilla Convention of Prevention of the Use and Illicit Traffic was signed.

In the nineties, the diplomacy against drugs traffic was very active inside the Andean Community and helped to the creation of institutions that aimed to reduce the coca fields in the member countries. The Andean policy against illegal drugs was founded on the consideration that the production, traffic, and consumption of those substances represent a problem of public health and affects the cultural, economic and social bases of the countries. In this regard, to execute the programs of such policy the Andean Community created the Executive Committee of Coordination in the Fight Against Drugs and in the year 2003 the Andean Committee for Alternative development (Molano, 2007, p.42-44).

As well, in the year 2001, decision 505 of the Andean Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs approved the Andean Plan of Cooperation for the Fight against Illicit Drugs and Conex Crimes. This instrument is actually a regional plan of action with comprehensive and realistic measures that, if applied correctly, could reduce the presence of illegal coca plantation in the studied countries. This starts with the conviction that the global problem on drug requires an integrated approach to tackle all of the issues that may be directly or indirectly related to the production, traffic, and consumption of drugs. The States also take a shared responsibility to fight against this transnational concern. It even puts itself as the center of the American strategy against drugs. To do this, it creates mechanisms cited before that not only includes coercive actions, but it also poses great importance to substitutive development, prevention, and rehabilitation. In this inclusive approach, it recognizes the existence and importance of connected criminality such as money laundering and arms traffic in the generation of violence and in the persistence of drug-related organizations (Andean Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Decision 505, 2001).

One of the most recent tools for the Andean Community members for the fight against illicit drugs is the Andean System of Information about Drugs. This enables Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru to share and compare statistic information of every government own policies and strategies about the different phases of the drugs cycle (Cárdenas, 2012). This is indeed helpful given that it enables the agencies in charge of the fight against drugs to create more effective policies that have been implemented before in other environments. As well, studies conducted by individual experts have been realized to categorize and characterize the impacts of drugs on specific groups in society[7]. However, agencies in each country are different, and the sharp increase in coca production in the last five years show that such tools are not helping to attack the essence of the problematic.

If we take just a look at the Andean institutions created to fight against illicit drugs, then it can be implied that such institutions are not effective given the constant and increasing presence of coca plantations in these three countries. However, the problem goes far beyond the institutional sphere, the reality in every and each country is very specific and they all present different particularities that are traduced in the persistence of the problem. Take the example of Colombia, where the announcement of the government in 2017 to give monetary benefits to families that voluntarily eradicate their coca plantations has prompt an increase in the coca crop levels in the country. This was caused by the sudden seeding of coca from families that did not have any interest in such crop before, just to be beneficiaries of the program (United States Department of State, 2017). Or the penetration of coca interest in the political institutions that serve as the ground to develop illegal activities in Bolivia. Therefore, to apply for one regional program in these countries is just an effort that will not see favorable results in the short and long-run.

One of the biggest obstacles for the successful implementation of policies that reduce the supply of illicit drugs such as cocaine and heroin in the Andean Region is the presence of an economic term known as balloon effect. The balloon effect is defined as repercussion or unexpected externalities of governmental policies against the dynamics of illegal markets. Drug cartels may respond to repressive policies changing their operational framework in ways such as the change of the production zones, the reduction, and decentralization of the production and the increase in the violence and incidence in the institutions (Raffo et Al., 2015, p.212). This may explain the persistence in the supply of illicit drugs to the markets in Europe and in the United States, and the impossibility to target the problem from the national scope alone. Evidence showed that the drop in the hectares of coca plantations in Peru and Bolivia, coincided with the increase in the hectares in Colombia (Raffo et Al., 2015). Such situation may have many generating elements, however, one of the strongest one assets that the strong repression in Peru during the Fujimori term caused the increase in the fields in Colombia in the nineties. As well, this can be visualized by the expansion of coca fields in Peru when they contracted in Colombia in the year 2010, due to the coercive prosecution in the second country in the years before during the term of President Uribe (see Annex 1).

Therefore, there are productive complementarities between the illegal economies in these three countries which greatly impacts the existence of balloon effects in the region. Based on this theory, one can prove that if the demand persists to be high, there is always going to be a supply to satisfy it. However, actions that aim to reduce the demand have also been applied, with little success. This may be given that the global demand for highly addictive drugs like cocaine and heroin is considered inelastic. Meaning that its consumption is not affected by the price of the market. this implies that the impact of any strategy of substitution development or eradication does not have the wanted results.

This being said, the most reliable solution to the balloon effect must be a regional approach, where the Andean Community stands as an ideal international mechanism to apply measures. Even, this phenomenon has also been indicated in individual studies in the Andean Community framework. Nevertheless, we experience that the problem goes far beyond that, and the complexity of the production networks and the particularities of the illegal market vertical integration pose a serious barrier that the Andean bureaucracy can’t overpass. Also, the presence of links in all the production chain makes it more difficult to target the problem as one, making it even more difficult from the regional perspective. Given that this links can recompose themselves in different geographical spaces and can mutate to better adapt their environment and context, is highly unprovable that a policy aiming to decrease such balloon effect would be effective.

First of all, in the Andean Region, there has being a preference for the subscription of bilateral international instruments over multilateral instruments. This is due to the more pragmatic character of the bilateral agreements. Most of these agreements count with a mechanism of implementation and evaluation of results that better suit the political and operational expectative of integration. Therefore, this is not an exception inside the illicit drug traffic framework of integration, where bilateral agreements are preferred over multilateral agreements. Take the example of Colombia as a glance of the importance of the models of integrations to solve the problem of drugs. Colombia has subscribed over eighty bilateral instruments of cooperation with different countries to prevent and suppress the use of illicit drugs and psychotropic substances. Meanwhile, this same country has only subscribed six agreements on the same topic with multilateral organizations, one of those being the Rodrigo Lara Bonilla Convention of the Andean Community (Ministry of Foreign Relations of Colombia, n.d). Even, Colombia has signed agreements on the same topic with each of every country that is part of the Rodrigo Lara Bonilla Agreement. Furthermore, Colombia has signed three different agreements related to illicit drugs with Peru. As well, many other enterprises have been pulled out to tackle the interregional traffic of drugs and other criminal activities outside regional platforms. For example, the proposal of creating an International base in the border of Colombia, Brazil, and Peru in 2017 with the support of the Southern Command of the United States (Nodal, 2017).

The preference of bilateral relations over multilateralism may be due to many reasons. Above there has been made reference of the practical conception of bilateral agreements. This, given that between two countries, is much easier to put into practice the articles stamped in the instruments. As well, much of this pragmatism is related with the state of the relations, that facilitates the execution or not of the instruments, which can explain the amount of cooperation and instruments between Peru and Colombia. Also, the noncompliance of the member countries with the decisions taken in the group`s components given the lack of supranational authority is one of the reasons for a prevalence of bilateral over multilateral instruments and pragmatism (Adkisson, 2003). Therefore, one could expect that such lack of authority of the supranational mechanism may be translated in little or no implementation of the policies compiled in the Decision 505.

On the other hand, as it has been proved in this article the supranational imaginary does not represent the reality in the countries. Therefore, even if there exists a structured plan to put into action, the actual implementation in zones that have been forgotten by public institutions is never going to render the desired outcomes. Even in the implementation of national policies against the cultivation of coca leaves, there are difficulties in the translation of the needs of the people in the afflicted zones and the public policies from governmental agencies (Semana, 2017). In Colombia, for example, the coca plantation problem is a conjugation between the economic rationality of poor peasants and the historical existence of violent criminal mafias. Therefore, the solution must take into account that peasants move between the gold illegal exploitation and the coca production based on the revenues either activity would earn from them. Also, there is a need for both meeting those mafias with the end of their existence and provide infrastructure in legal areas to support the economic activities of legal crops. As well, in Bolivia, the plantation of coca must not be seen as an opportunity of enrichment and has to be kept as a traditional usage. By acquiring this into the imaginaries of the people and agencies in the country, one could hope for the diminishing of the illegal production of coca. Also, in Peru, public authorities must have into account the possible implications of the balloon effect and the possible entrance of criminal organization moving out of Colombia as it has been observed previously. Nowadays, criminal organization are truly transnational, having members of different nationalities and stablishing in many countries. By preparing and strengthen their capabilities there should be a reduction in the production, and not just react to the ongoing outcomes of already installed illegal systems.

As well, as it has been shown before, starting from different points make it difficult to apply a common regional policy with commonly expected outcomes in each country. Each country must, at first, apply the policy that better adapts to their reality. The regional instrumentalities established in the Andean Community must stand in the way of national practices and become a disadvantage that fixes illogical and inconsistent policies to the countries, but rather these integration spaces should favor the free implementation of national and bilateral policies and offer all the tools necessary to help to each effort. By doing this, each policy can better adapt to the mutuality characteristic of criminality and target them more efficiently before they grow stronger. Therefore, countries can avoid the overlap of policies, rules, and institutions that may affect more the effectivity of agencies. Much of the articles in different global and regional institutions are the same, addressing the same problem with the same typical formulas, having the same outcomes. Then, more institutionalism must pose a problem, and countries must go further and innovate autonomously helped by regional structures.

Conclusion

Coca production in the Andean Region has historically been related to traditional cultures of indigenous communities. Nevertheless, in recent history that culture has transformed to be one of violence and economically driven. This situation pushed from the last century by the demand for cocaine in Europe and North America. To tackle the problem there must be a multilateral approach since it is a transnational issue. However, the problem with drugs is very complex itself and the institutions created to tackle it have not the capabilities to stop the supply of cocaine in the Andean countries. The problem comes from a different perception and approach from each different country, that experiences the coca production in different levels. This conjugates with the inability of supranational authorities that don’t translate the different national realities into regional policies, which harms trust in regional institutions and implies the use of bilateral mechanism as the only way to tack transnationality in subjects like the balloon effect and the mutation of criminality. Therefore, what is needed to be done is a reconfiguration of the regional institutions that support and complement each individual and bilateral effort and innovate in some way to tackle the problem before it reassembles and transform into a rooted problem. This, can be done with the help of other regional organizations, that put into the service of the Andean Community expertise and tools to tackle the drugs problem in these countries.

Annexes

Source: Created by the author with information of the Office of National Drug Control Policy of the White House, retrieved may 5th, 2022.

Source: Created by the author with information from the Ministry of Defense of Colombia, INEI of Peru and INE from Bolivia, showing the low correlation between the variables of coca hectares and homicides in Peru. However, it is important to have in mind that the variable Homicides is affected by many other variables other than coca plantation.

References

Adkisson, R. (2003) The Andean Group: institutional evolution, intraregional trade, and economic development, Journal of economic issues, vol. XXXVII Nº2. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2003.11506584

Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (2017) International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Drug and Chemical Control, United States Department of State, retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/268025.pdf

Balzacq, T. (2005) The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience and Context, European Journal of International Relations, 171-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105052960

Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998) Security: a new framework of analysis. Lynne Rienner Publisher. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685853808

Campbell, D. (1992) Writing security: United States foreign policy and the politics of identity. University of Minnesota Press.

Cárdenas, R. (2012) Comunidad Andina frente al problema de las drogas, Portafolio, Bogotá.

Comunidad Andina de Naciones (1986) Convenio “Rodrigo Lara Bonilla” entre los países miembros del Acuerdo de Cartagena, sobre cooperación para la prevención del uso indebido y la represión del trafico ilícito de estupefacientes y sustancias psicotrópicas, retrieved from: http://apw.cancilleria.gov.co/Tratados/adjuntosTratados/C907E_OTROS_M-CONVRODRIGOLARABONILLA1986-TEXTO.PDF

Consejo Andino de Ministros de Relaciones Exteriores (2001) Decisión 505: Plan Andino de cooperación para la lucha contra las drogas ilícitas y delitos conexos, Comunidad Andina de Naciones, Valencia, Venezuela.

Crick, E. (2012) Drugs

as an existential threat: An analysis of the international securitization of

drugs, International Journal of Drugs Policy, 23, 407-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.03.004

PMid:22554852

Cubides, O. (2014) La violencia del narcotráfico en los países de mayor producción de coca: los casos de Perú y Colombia, Papel Político, 19(2), 657-690. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.PAPO19-2.vnpm

Diaz, B. (2002) Política exterior de los EE.UU. hacia Colombia: el paquete de ayuda de 1.300 millones de dólares de apoyo al Plan Colombia y la Región Andina, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, América Latina Hoy, 31, 2002, pp. 145-186.

Falconi, J. (2012) Informe final análisis de los factores económicos que inducen al agricultor de las zonas cocaleras peruanas a la decisión de cultivar o no coca, Programa Anti-drogas en la Comunidad Andia PRADICAN, retrieved from: http://www.comunidadandina.org/DS/Inf.%20Eco%20coca%20Per..pdf

Office of the High Commissioned For Peace (2016) Final Agreement for the End of the Armed Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Long-lasting Peace, retrieved from: http://www.altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co/procesos-y-conversaciones/Documentos%20compartidos/24-11-2016NuevoAcuerdoFinal.pdf

Garzón, J. (2017) ¿En qué va la sustitución de cultivos ilícitos? Informe trimestral #2, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, retrieved from: http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1596

Guerrero, R. (2013) Informe sobre la implementación de programas de desarrollo alternative en zonas de influencia de la coca y sus impactos en los países de la subregión andina, Programa Anti-drogas en la Comunidad Andina PRADICAN, retrieved from: http://www.comunidadandina.org/DS/Inf.%20Inv.%20Zonas%20Coca.pdf

Jelsma, M. And Youngers, C. (2017) Coca and the Colombian peace accord: a commentary on the pilot substitution project in Briceño, Advocacy for Human Rights in the Americas, retrieved from: https://www.wola.org/analysis/coca-colombian-peace-accords-commentary-pilot-substitution-project-briceno/

Martinez, C. (2012) The “war on drugs” and the “new strategy”: identity constructions of the United States, U.S. drug users and Mexico, Mexican Law Review, (V), 245-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1870-0578(16)30025-7

Mansilla, H.C.F. (2009) Neoliberalismo, drogas y valores sociales: el debate en el área andina a partir de 1990, Revista de Ciencias Sociales 123-124, pp. 93-103.

Ministry of Foreign Relations of Colombia (n.d.) Library of International Treaties, retrieved from: http://apw.cancilleria.gov.co/tratados/SitePages/BuscadorTratados.aspx?TemaId=37&Tipo=B

Molano, G. (2007) El dialogo entre la Comunidad Andina y la Unión Europea sobre drogas ilícitas, Colombia Internacional 65, ene-jun 2007, pp.38-65. https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint65.2007.02

Office of National Drug Control Policy (2021) ONDCP releases data on coca cultivation and production in the Andean Region, retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/briefing-room/2021/07/16/ondcp-releases-data-on-coca-cultivation-and-potential-cocaine-production-in-the-andean-region/

Presidencia de la República (May 29th, 2017) Decreto Ley 896 de 2017: por el cual se crea el Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos de uso Ilícito, retrieved from: http://es.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/DECRETO%20896%20DEL%2029%20DE%20MAYO%20DE%202017.pdf

Niño, C. (2011) Crimen organizado y gobernanza en la región andina: cooperar o fracasar, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Quito.

Raffo, L., et Al. (2016) Los efectos globo en los cultivos de coca en la Región Andina (1990-2009), Apuntes del CENES (35) 61, pp. 207-236. https://doi.org/10.19053/22565779.3426

Semana (2017) No veo la estrategia para enfrentar los cultivos de coca, Bogotá, retrieved from: http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/experto-en-narcotrafico-daniel-rico-critica-politica-de-cultivos/517393

Weldes, J. (Ed.). (1999). Cultures of insecurity: states, communities, and the production of danger (Vol. 14). U of Minnesota Press.